.io considered harmful

By Cariad Eccleston • 👋 @cariad@indiepocalypse.social • ✉️ cariad@cariad.earth

This article has content warnings for animal abuse, ethnic cleansing and suicide.

The .io top-level domain funds and legitimises Britain’s exile of the Chagossian people from their homeland. Here’s the history and the facts.

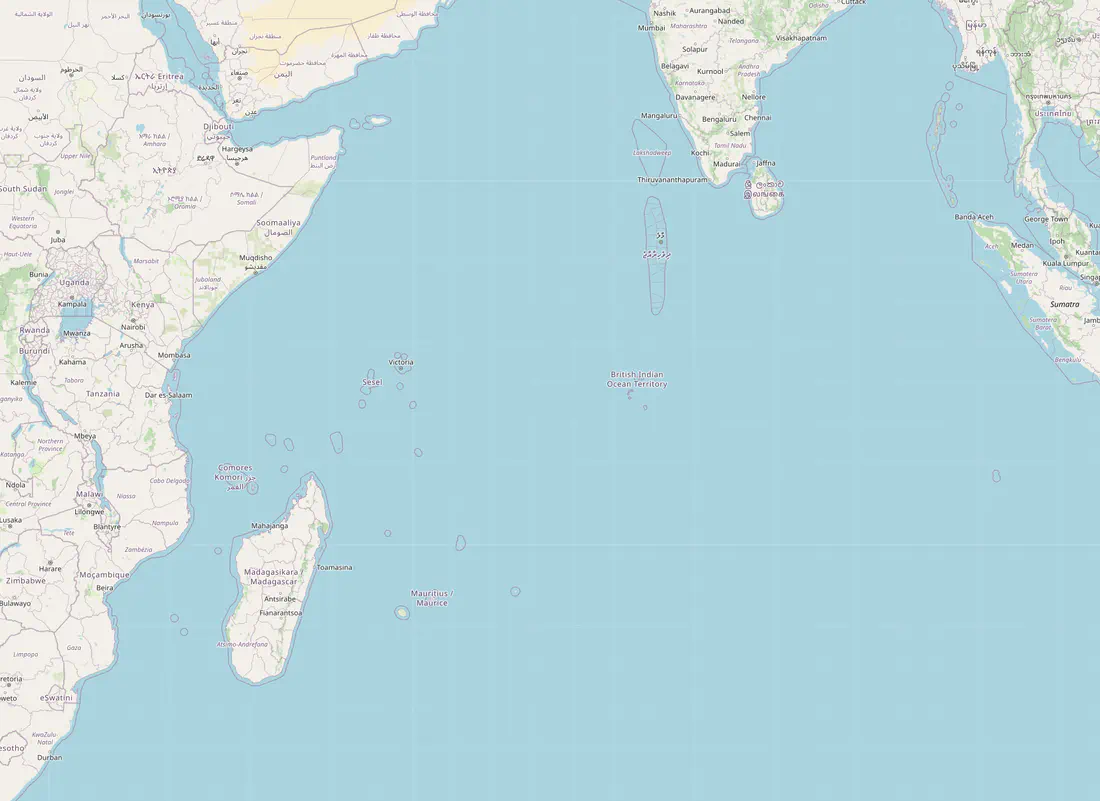

Out in the middle of the Indian Ocean lies the small coral Chagos Archipelago.

With the coastlines of Africa, Asia and Antarctica thousands of kilometres distant, the archipelago is amongst the most isolated on the planet. The islands are tiny, too, with a total land area of 56 km²; about half the size of Walt Disney World Resort in Florida.

But despite the archipelago’s size and isolation, it was home–for a time–to a thriving community.

A short history lesson

The first Europeans to stake a claim to the Chagos Archipelago were the French. They settled the nearby Isle de France in 1715. By 1793, a French coconut plantation housed the first permanent settlement on the archipelago’s largest island, Diego Garcia.

This being an 18th Century European settlement, of course it was built on the backs of slaves. The colony was French, but the people were Malagasy and Mozambican1, and all were governed from Isle de France.

After Napoleon’s defeat in 1814, the French ceded Isle de France and its dependencies to Britain2. Britain reinstated the Isle’s Dutch name, Mauritius, and continued to govern the Chagos Archipelago and its plantations from there.

After the abolition of slavery in 1835, many now-freemen stayed on the archipelago and were joined by labourers from India. Beautiful people being beautiful people, they were fruitful and multiplied. New families made the archipelago their home, and an integrated Chagossian society blossomed for generations.3 By the 1960s the archipelago was home to some 2,000 people.

In the incredible documentary “Stealing a Nation”4, journalist John Pilger asked Charlesia Alexis5 about her fondest memories of Diego Garcia6:

We could eat and drink everything, we never lacked for anything. And we never bought anything, except for the clothes we wore.

In that same documentary, Rita Élysée Bancoult reminisced:7

I had dogs which I brought to the beach with me. At low tide they would go out and catch fish and bring them in and lay them at my feet.

While the islanders relied on their governing island Mauritius for trade and medical treatment, they were largely and comfortably self-sufficient. Life was, by their own accounts, good.

Conspiracy

The end of World War II in 1945 led to the start of the Cold War. Soviet influence grew across Europe and Asia, and the United States of America sought to expand too.

And she had just the spot in mind.

No matter where in the world the next inevitable war was to break out, those idyllic coral islands smack in the centre of the Indian Ocean would be the perfect staging platform8 for attacks against a dozen countries' supply lines, communication hubs and military targets.

But how could the United States acquire the archipelago? The land was Mauritian territory, and – even though Mauritius was a British territory–Britain had no claim over the islands. No matter what the United States' offered her war-time ally, the land wasn’t legally Britain’s to trade.

And so, Britain traded the land illegally.

On November 8th, 1965, the British Foreign Office redrew the map. Public servants in London created, on paper, a new British territory–the British Indian Ocean Territory9–which encompassed the Chagos Archipelago, then transferred governance of the islands from Mauritius directly to London.

By the Foreign Office’s reckoning, the islands were now British. And in exchange for a $14 million discount on a nuclear missile10, the British Indian Ocean Territory was leased to the United States of America.

But what about the Chagossian people living on those islands?

Terror

The American military-industrial complex was not amenable to sharing the islands.

The people were removed; first by terror, then deceit, then force.

Robin Mardemootoo, lawyer for the Chagos Islanders, explained11 the opening strike against the people:

The British and American authorities implemented a policy decision that was aimed at depriving that community–in the Chagos–from basic supplies. No milk, no dairy products, no oil, no sugar, no salt, no medication, no more of the things you use in life.

When the blockade didn’t scare enough Chagossians away, Sir Bruce Greatbatch–Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George, Member of the Order of the British Empire, Governor of the Seychelles and interim administrator of the British Indian Ocean Territory–ordered all the dogs on Diego Garcia to be killed.

Almost a thousand pets and hunting animals were rounded up and gassed with the exhaust fumes of American military vehicles. The people were threatened with the same if they didn’t leave.12

When terror didn’t work, Britain resorted to deceit. Islanders who left the archipelago were denied return. Many, like Charlesia Alexis, had no idea when travelling to Mauritius for medical treatment that they’d never see their homes again.

And finally, when terror and deceit hadn’t been enough, the islanders were removed by force.

Exile

At 1pm on October 15th, 197113, the remaining people of Diego Garcia were summoned to the office of Sir Greatbatch’s magistrate, John Rawling Todd14. They were told they were to be loaded onto the cargo ship MV Nordvær and immediately expelled from their homeland.

They were allowed one suitcase each. Anything of cultural, emotional or financial value that they couldn’t carry had to be abandoned. Sir Greatbatch demanded that the horses ride on-deck, while each family was permitted one mattress and forced to sleep on the ship’s cargo of bird shit.

In an instant, not having bank accounts or currency of significant value, the Chagossians were poverty-stricken; no farms, no ocean to fish, no money, no homes.

The Nordvær sailed to the Seychelles, where the Chagossians were marched uphill to a prison and held until passage to Port Louis, Mauritius, was arranged. Then, at Port Louis, they were dumped and abandoned on the docks.

Cassam Uteem, former President of Mauritius, recalls:15:

Some of them stayed on the docks, waiting for the next ship to take them back home. There was never to be a ship to take them back home.

Eventually, they were taken to the derelict Estate Beau Marchand housing estate. They were given no water, no electricity, no doors, and no windows.16

Many of the islanders died; of poverty and–in their own words–of “sadness”.

Of heartbreak, despair, and suicide.

Those who lived couldn’t afford to pay for funerals.

By the end of 1975, the expulsion and exile of the Chagossian people was complete. A survey showed 26 families had died together in poverty. Young girls were forced into prostitution to survive. 9 people committed suicide.17 And Mauritian slums are still prisons to Chagossians today.

This was nothing less than ethnic cleansing.

The war machine

Today, the archipelago’s two-thousand Chagossians have been replaced by two-thousand military personnel.

Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia18 is owned by the British Ministry of Defence, leased to the United States Navy, and operated together.

“One Island, One Team, One Mission,” they say.

Nearly 4 km of Diego was paved into a runway19 where American bombers have launched attacks on Iraq20 and Afghanistan. There are piers and warehouses to support aircraft, ships and submarines. The island even hosts a satellite tracking station codenamed “REEF”21.

How did they get away with this?

They knew it was illegal

From the very beginning of the conspiracy to expel the Chagos Islanders, the British and United States authorities knew it was illegal.

They anticipated several challenges, two of which were:

- The detachment of colonial territory.

- The United Nation’s “sacred trust”.

First, the detachment of colonial territory. United Nations Resolution 1514 (XV)22 states:

[…] any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

In other words, in the opinion of the United Nations General Assembly and recorded in Resolution 206623 in 1965, Britain broke international law when she detached the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritian territory and reassigned it to British Indian Ocean Territory.

Mauritius did not, at the time, have independent legislative or executive power. Without the power of free and genuine expression, the consent of the people could not have been queried or known.24

Sacred Trust

The second legal challenge concerns the United Nations' “sacred trust”.

Chapter XI of the UN Charter25 requires member states to recognise that “the interests of the inhabitants of [their] territories are paramount” and accept a “sacred trust” to promote their peoples' well-being.26

It goes without saying, the forced expulsion of the British citizens of the Chagos Islands from their homelands into abject poverty utterly violated international law.

Britain’s defence was to claim–to lie–that the Chagos Archipelago was uninhabited when it was transferred into British Indian Ocean Territory administration. Now that British Foreign Office memoranda of the time are on the public record, we can see the lie for ourselves.

Foreign Office memorandum, July 1965, records:27:

People were born there, and in some cases their parents were born there too. The intention is, however, that none of them should be regarded as being permanent inhabitants of the islands. […] The legal position of the inhabitants would be greatly simplified from our point of view, though not necessarily from theirs, if we decided to treat them as a floating population.

By “floating population”, the Foreign Office meant to convince the world that the Chagossians were contract workers temporarily living on the island for employment, with no claim that the islands are their homeland.

Another Foreign Office memorandum, in November 1965, reinforced the lie and Britain’s lack of concern for UN condemnation:

There is a civilian population. In practice, however, I would advice a policy of “quiet disregard”–in other words, let’s forget about this one until the United Nations challenge us on it.

They tried

And the United Nations–and others–did challenge Britain. Repeatedly.

In 2019, the International Court of Justice ruled that the UK’s occupation of the Chagos Islands is unlawful28. The UN passed Resolution A/73/L.8429 to demand that the United Kingdom unconditionally withdraw its administration from the area within six months.

In 2000, the United Kingdom’s own High Court ruled that Britain should allow the Chagossians to return home.30

In 2021, Case #2831 of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled that32:

[…] it is inconceivable that the United Kingdom, whose administration over the Chagos Archipelago constitutes a wrongful act of a continuing character and thus must be brought to an end as rapidly as possible, and yet who has failed to do so, can have any legal interests in permanently disposing of maritime zones around the Chagos Archipelago by delimitation.

And:

It follows that, despite the United Kingdom’s ongoing and unlawful colonial administration of the Chagos Archipelago, there can be no doubt that the Chagos Archipelago forms an integral part of the territory of the Republic of Mauritius and that there is no dispute with the United Kingdom as regards sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago.

It never ends

So, with all these rulings, what’s Britain to do?

Terminate the United States' lease on the islands and tear down the base?

What do you think?

Britain’s response was to designate the territory a nature reserve–the Chagos Marine Protected Area33–to be protected from human habitation.

But now, is it really fair of me to imply that the creation of the Chagos Marine Protected Area was just a disgusting ploy to prevent the Chagossians returning home? Couldn’t it just be a rare and genuine political effort to save a natural environment?

We could believe that, if not for Wikileaks.

On May 15th, 2009, a cable34 intercepted from Britain described the then-proposed reserve:

HMG [Her Majesty’s Government] would like to establish a “marine park” or “reserve” providing comprehensive environmental protection to the reefs and waters of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), a senior Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) official informed Polcouns on May 12. […] He said that the BIOT’s former inhabitants would find it difficult, if not impossible, to pursue their claim for resettlement on the islands if the entire Chagos Archipelago were a marine reserve.

Colin Roberts, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Director of Overseas Territories, is quoted as:

[…] according to [Her Majesty’s Government’s] current thinking on a reserve, there would be “no human footprints” or “Man Fridays” on the BIOT’s uninhabited islands. He asserted that establishing a marine park would, in effect, put paid to resettlement claims of the archipelago’s former residents. Responding to Polcouns' observation that the advocates of Chagossian resettlement continue to vigorously press their case, Roberts opined that the UK’s “environmental lobby is far more powerful than the Chagossians' advocates.”

And if the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s disdain for the Chagossian people wasn’t obvious enough:

Roberts emphasized. “We do not regret the removal of the population,” since removal was necessary for the BIOT to fulfill its strategic purpose, he said. Removal of the population is the reason that the BIOT’s uninhabited islands and the surrounding waters are in “pristine” condition.

The cable ends with:

Establishing a marine reserve might, indeed, as the FCO’s Roberts stated, be the most effective long-term way to prevent any of the Chagos Islands' former inhabitants or their descendants from resettling in the BIOT.

Angry, yet? Let’s start talking about what you can do. Or, stop doing.

IO

The International Organization for Standardization35 (ISO) is an international, non-governmental organisation that develops and describes shared understandings of our world.

ISO 9660, for example, describes the structure of CD-ROM disks. ISO 8601 describes date and time representation. And since 1974, ISO 316636 has described an ever-growing set of 2-character codes to represent the countries and territories of the world.

The United States of America, for example, was assigned “US”. Britain got “GB”. And the British Indian Ocean Territory was given “IO”37.

In March 1994, the Internet was young but growing fast. There were only seven top-level domains available back then–".com”, “.org”, “.net”, “.int”, “.edu”, “.gov” and “.mil”–and the webizens of the information superhighway hungered for more variety.

In RFC 159138, Jon Postel proposed the addition of country code top-level domains, which would use ISO 3166 as a basis and would allow governments to use and monetise as they wished.

The proposal came to pass. The United States of America was given the power to sell and profit from “.us” domains. Britain was given “.uk” domains. And she got her stolen territory’s “.io” domains, too.

And so, finally, I reach my point.

Every “.io” domain you buy funds a government committing crimes against humanity39. Every “.io” domain you renew legitimises and reinforces the continued exile of the Chagossians.

What happens now?

I’ve got nothing but sympathy for folks who bought a .io domain in good faith before they learned about the criminality behind it.

In fact, in a way, the last thing I want is to tarnish the .io domain.

There’s a lot to be done before this wrong has been righted, but a part of that has got to be the redirection of profits from .io sales and renewals from the British government to the Chagossian people. And then, if the Chagossian people are amenable to global sales of .io domains, for the name to enjoy a second renaissance and financially support the right people.

My dreams are naive, sure.

For my part, I’m working on migrating all my email from @cariad.io to @cariad.earth. It’s a pain, but it’s worth it.

If you’re able to, stop buying and renewing “.io” domains. Next time you’re asked to vote, find out how your candidates feel about the exile of the Chagossians. Read what The Chagos Refugees Group40 has to say.

And for fuck’s sake, look out for your fellow human beings.

Edited on 4 November, 2023: J.A. Pipes kindly pointed out that I’d used “Mauritanian” and “Mauritian” interchangeably, and I’m happy to correct the record. No references to Mauritania were intended, and I apologise for the error.

World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Mauritius : Chagossians/Ilois ↩︎

Republic of Mauritius - History / The British period (1810-1968) ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, 2004. ↩︎

Charlesia, with Rita Élysée Bancoult, Louis Olivier Bancoult and Aurélie Marie-Lisette Talate, founded the Chagos Refugee Group. She sadly passed away on December 16th, 2012, never having been allowed to return to Diego Garcia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlesia_Alexis ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 04:30. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 04:50. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 32:20. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 06:25. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 07:00. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 09:02. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 11:24. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 11:55. ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 14:15. ↩︎

Commander, Navy Installations Command, “Welcome to Navy Support Facility Diego Garcia” ↩︎

United Nations, “General Assembly Welcomes International Court of Justice Opinion on Chagos Archipelago, Adopts Text Calling for Mauritius’ Complete Decolonization” ↩︎

United Nations, “United Nations Charter, Chapter XI: Declaration Regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories” ↩︎

United Nations, “Non-self-governing territories: a sacred trust” ↩︎

“Stealing a Nation”, timestamp 23:20. ↩︎

United Nations, “General Assembly Welcomes International Court of Justice Opinion on Chagos Archipelago, Adopts Text Calling for Mauritius’ Complete Decolonization” ↩︎

United Nations, “Advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on the legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 : draft resolution / Senegal [on behalf of the Group of African States]" ↩︎

Equal Times, “Will the UK ever let Chagos islanders return home?" ↩︎

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, “Dispute concerning delimitation of the maritime boundary between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius/Maldives)" ↩︎

1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, “Amended Preliminary Information Submitted by the Republic of Mauritius Concerning the Extended Continental Shelf in the Northern Chagos Archipelago Region” ↩︎

Wikileaks, “HMG FLOATS PROPOSAL FOR MARINE RESERVE COVERING THE CHAGOS ARCHIPELAGO (BRITISH INDIAN OCEAN TERRITORY)" ↩︎

International Organization for Standardization, “3166:IO” ↩︎

Scottish Legal News, “Edinburgh meeting hears Britain’s refusal to allow Chagos Islanders to return home is ‘crime against humanity’" ↩︎